Thrust, drag… Weight, lift.

It’s all a balancing act, revolving around the wing.

I’ve always struggled with how I should explain flight. For a flight instructor, that’s not a good thing. There is no more important concept.

Do you start with how lift is created? That makes sense. But then you get in to stability and all that entails, flight controls and maneuverability… And down the rabbit hole we go. There is a reason for that.

When trying to understand flight, it’s important to understand that almost everything affects… everything. I know that I am supposed to present things in simple terms, but… Sorry about your luck. You’re going to have to think about this for a while.

Fortunately, at a given point in time, there are a couple constants.

Gravity is absolute. Always has been, always will be. Weight (or MASS) changes over time in an airplane due to fuel burn, but for the sake of this discussion, let’s assume that we are talking about a moment in time. Mass, and the center of mass (center of gravity) is also static for this discussion, although this can also shift over time as we burn fuel.

We’ll assume that we are not flying an F-14, with its movable wing… So the aerodynamics will only change with the application of basic flight controls. That’s plenty to make the airplanes we fly do what we want them to do.

Okay. You are a pilot in your element. Cruise flight. Straight, level… Unaccelerated. 120 knots, covering two miles per minute.

It’s a calm day in stable air. The airplane is trimmed such that you can take your hands off the flight controls and nothing changes.

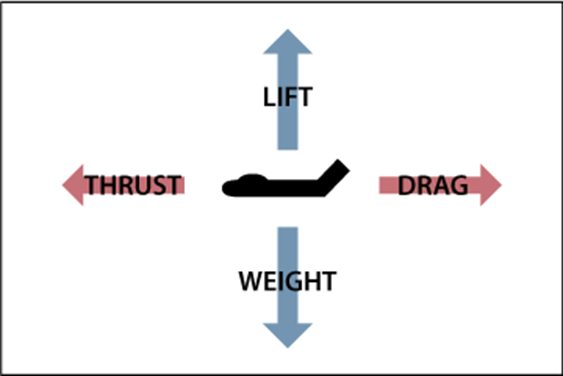

Lift equals weight and thrust equals drag.

Perfect.

So, the rote answer to the ‘What are the Four Forces of flight?’ question is “Lift, weight… Thrust, drag.” Both pairs opposing each other. How can things be so serene and smooth, if these forces, collectively equaling thousands of pounds, are in constant conflict?

Not to get too philosophical, but all things in life seek equilibrium. Balance.

The water in rivers seek the lowest point they can reach, typically the ocean. The air moves around us because it is seeking the lowest pressure it can find, so wind moves from high pressure areas to low pressure areas… Both trying to find balance and come to rest.

The airplane we fly is no different. It has static and dynamic stability characteristics that cause it to seek ‘unaccelerated flight’, a state at which its airspeed is constant, and it’s vertical speed is constant.

Let’s begin to eat the elephant of aerodynamics and flight with a single easily understood bite: The wing.

The wing extends laterally from the fuselage of the airplane and have a shape that, when the airplane is moving forward through the air at sufficient speed, produces lift. When sufficient speed and angle on the relative wind is achieved, enough lift is developed to overcome the weight, or mass, of the airplane, and it takes flight.

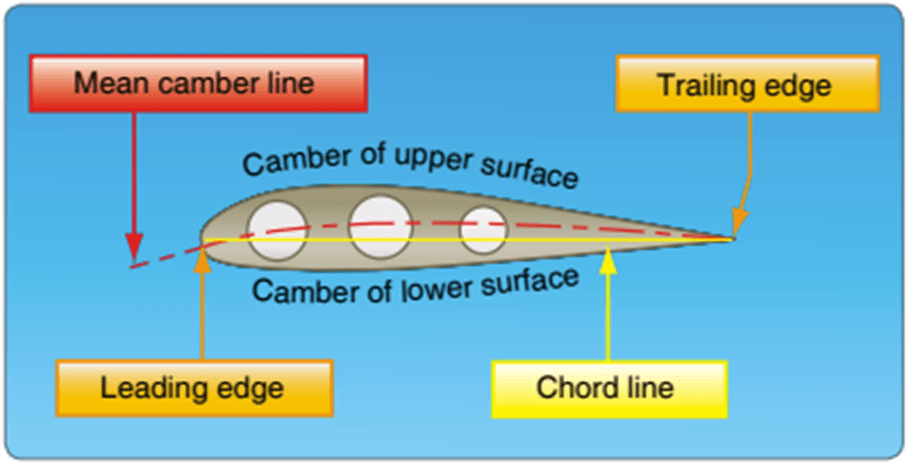

If you were to slice through the wing from the top, and then look at it from the side, you would see the shape of the wing that makes lift, called the airfoil.

There are many different shapes that aeronautical engineers may choose in order to achieve certain flight characteristics. That said, there are dimensions and curves that are universal (See Figure above).

The Leading Edge and Trailing Edge are simply the front and back of the airfoil. The “Camber” of the upper and lower surfaces describe the shape of the surfaces. The Chord Line is a straight line between the leading edge and trailing edge.

The mean camber line is a line that is equidistant between the upper and lower surfaces of the wing.

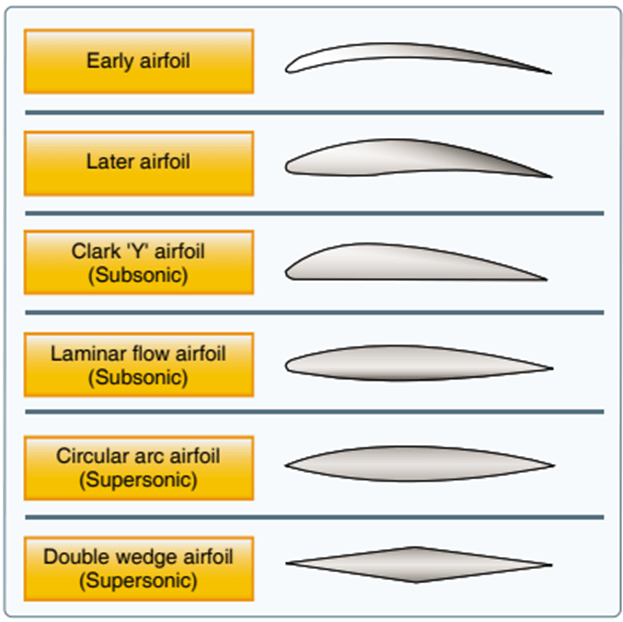

Some sample airfoil shapes are below:

Piper Cub or Airliner… It’s all a balancing act revolving around the wing.

Hi, I’m Lillie. Previously a magazine editor, I became a full-time mother and freelance writer in 2017. I spend most of my time with my kids and husband over at The Brown Bear Family but this blog is for my love of food and sharing my favorites with you!

Subscribe to My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

The Clark ‘Y’ airfoil is similar to airfoils used in general aviation aircraft such as the Cessna 172. The Piper Cherokee attempted to use a laminar flow wing, but was only partially successful… But that is a discussion for another time. The important thing to remember is that the airfoil design is based on the weight, speed and purpose of the airplane.

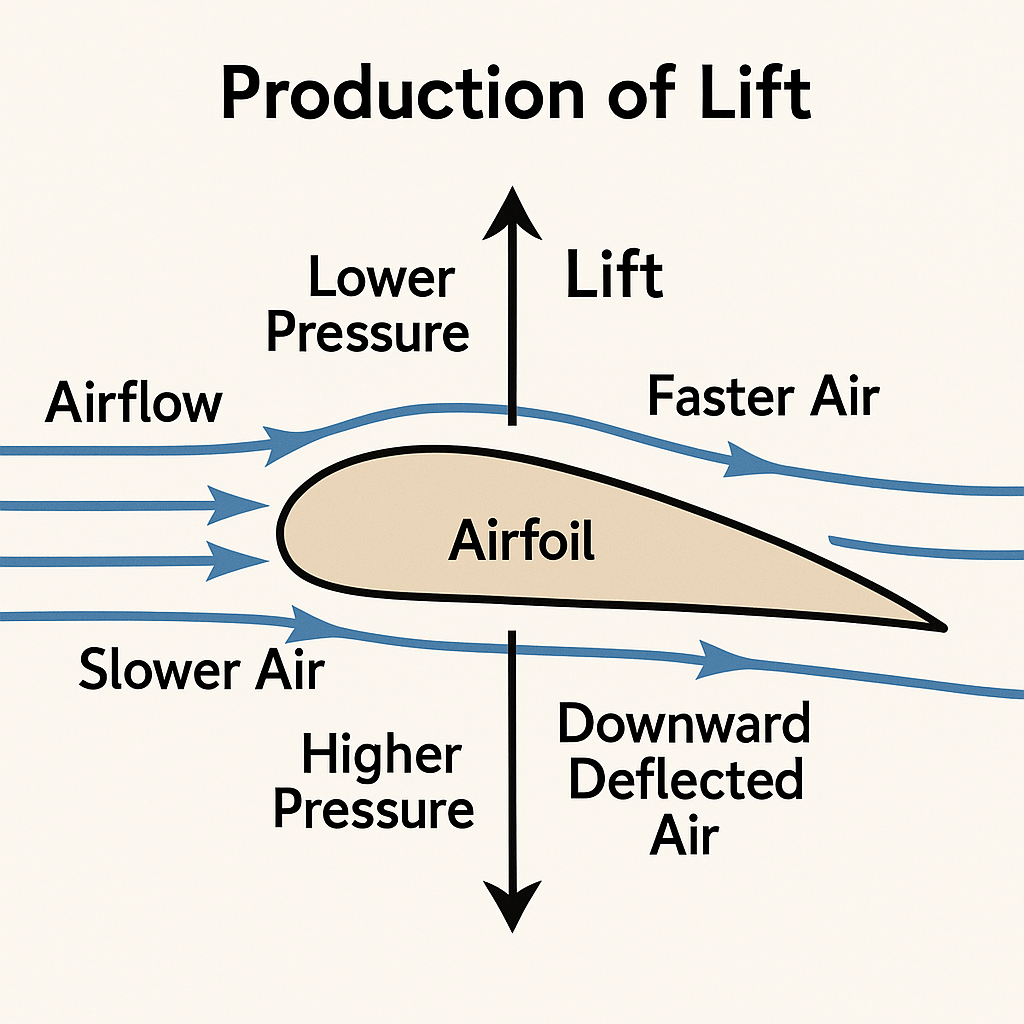

Wings produce lift through the interaction of airflow with their specially curved shape, known as an airfoil. As air flows over the wing, the curvature of the upper surface causes the air to travel faster than the air beneath the wing. According to Bernoulli’s principle, this faster-moving air creates lower pressure on top of the wing, while the slower air underneath maintains higher pressure. This pressure difference generates an upward force called lift. Additionally, Newton’s third law contributes to lift: as the wing deflects air downward, the reaction is an equal and opposite force pushing the wing upward. Together, these aerodynamic principles enable an aircraft to overcome gravity and remain airborne.